After years of breakneck growth in capacity and uptake that has seen wind power delivering a fifth of Germany's total energy production, vocal “not-in-my-backyard” opposition by residents and a lack of government support have seen investments shrink in the sector.

More than 600 citizen initiatives have sprung up against the giant installations, with a district called Saale-Orla even offering €2,000 to anyone taking action to get expert opinions opposing wind farms.

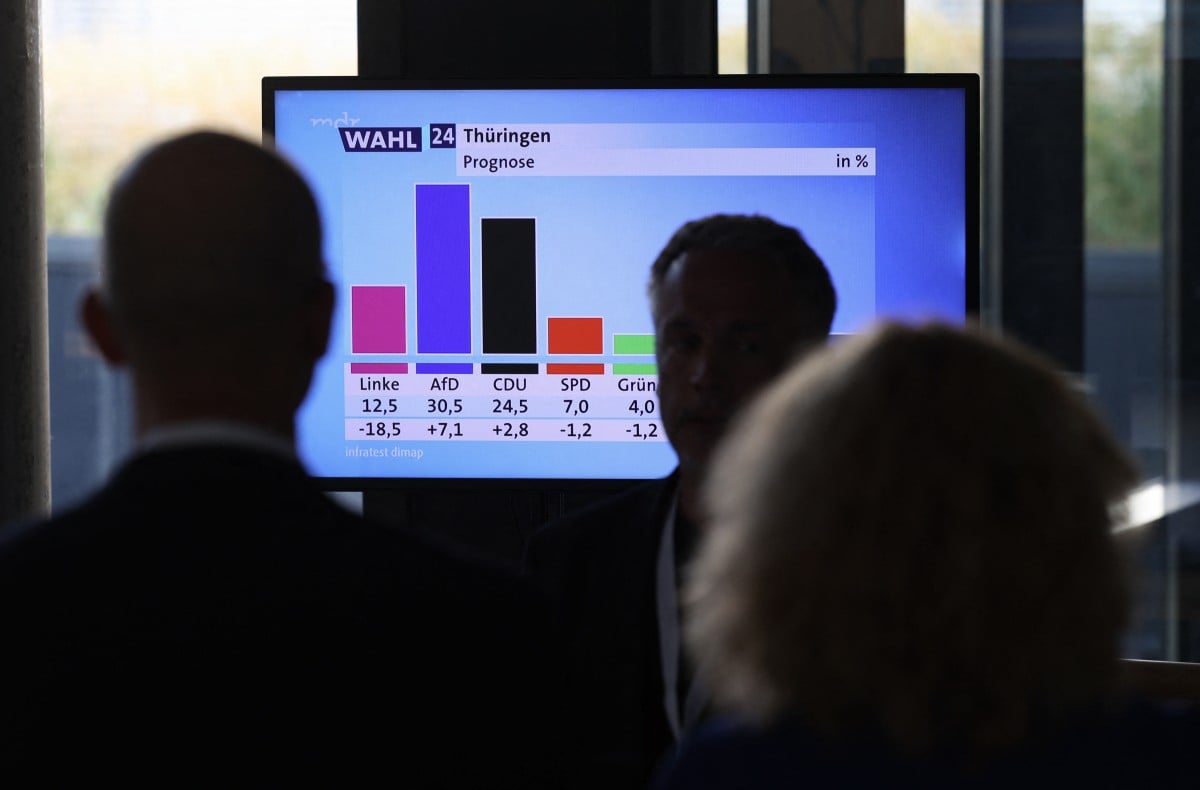

The far-right AfD party, branding itself as the climate-sceptic outfit, had seized on the topic during state elections in Brandenburg, saying it stands by residents steamrollered by wind energy corporations.

Against the backdrop of bitter division, expansion in Germany's wind power production capacity plunged in 2018 to half that in 2017 as companies struggled to obtain permission to build.

And only a few dozen new turbines were installed since the beginning of this year, down 82 percent from a year ago, said Germany's Wind Energy Association (BWE).

And repeatedly every quarter, official tenders for electricity production have returned undersubscribed — a “worrying” trend, said the Federal Network Agency.

“With regard to the expansion of onshore wind power, Germany has moved from the fast to the breakdown lane,” said Achim Derck, president of the German Federation of Chambers of Commerce and Industry (DIHK).

For BWE president Hermann Albers, the implication is clear – “this development calls into question the success of Germany's energy transition.”

READ ALSO: Brandenburg elections: In east German rust belt, economic fears boost far-right

Ending subsidies

Market players said the tipping point came in 2016 when Germany amended its Renewable Energy Act.

After almost two decades of providing subsidies to prop up the nascent sector, Chancellor Angela Merkel's government decided that the industry was now sufficiently mature and began withdrawing support.

With obtaining building permits often taking years thanks to stubborn local opposition, projects took even longer to recoup costs, also shifting the calculation by firms whether to invest.

A sign saying 'no' to wind power in the Bavarian Forest region. Photo: DPA

A sign saying 'no' to wind power in the Bavarian Forest region. Photo: DPA

In the months following the 2016 amendment, the wind power sector shed 26,000 jobs in Germany, more than in the dwindling coal industry, according to figures provided by the Bundestag, Germany's lower parliament.

“We have sounded the alarm, but why the German government has chosen to go down this path remains a mystery to this day,” said BWE head Albers, who feels that Berlin had put too much “emphasis on costs” in the transition to green energy.

'Tip of the iceberg'

But the crisis in the sector has now shot back up to the top of the political agenda as youths took on the climate emergency with their vocal Fridays for Future protests, fuelling support for the Green party.

In order to meet the government's target of sourcing 65 percent of Germany's energy from renewables by 2030, the proportion of wind power will have to grow from around 20 percent currently to replace coal, which still makes up close to a quarter of the mix.

READ ALSO: 'We are heading up': Why the Green party is gaining support in eastern Germany

Ahead of a broader government announcement on September 20th on its climate strategy, Economy Minister Peter Altmaier (CDU) will host crisis talks on Thursday in Berlin with key players in the wind energy sector.

With 5,000 first generation wind turbines also up for renovation, the stakes are high.

For some however, the political attention has come too late.

“We've been asking for help for months. I don't think the government understands that it is destroying an economic ecosystem that is a source of cutting-edge engineering and innovation, that has taken time to create and has made Germany famous,” Yves Rannou, head of the German wind turbine manufacturer Senvion, told AFP.

The company said last week that it is closing down, as its German revenues, which once represented 60 percent of its revenues, have shrunk to just 20 percent.

“We are only the tip of the iceberg, the first to get down on our knees, but not the last,” Rannou warned.

By Daphne Rosseau

Please whitelist us to continue reading.

Please whitelist us to continue reading.

Lots of questions and problems raised, but few answers. Here’s some:

1) What do those people who forced Merkel to shut down German nuclear power now say? They have a big responsibility to provide answers.

2) When is Germany’s massive dependence on burning coal going to be eliminated?

3) What precisely IS the objection to wind power? The article doesn’t explain. Is it the appearance of the turbines? If so, then objectors should be asked “Do you actually want to be able to turn your kettle on in the morning? If so then either offer alternatives or shut up. One of the advantages of wind turbines is that they are relatively quickly dismantled if/when another form of clean energy comes along, as it surely will. They are actually the most transient of objects. Just imagine having to dismantle a nuclear power station!